We’ve been really busy figuring out how to teach our kids and support our community as the pandemic worsens in India. The last 6 months seem unbelievable and we’re sometimes surprised that KHEL, along with everything else, hasn’t just collapsed. We have had moments of despair when we’ve wondered if KHEL would survive another month, or if we would lose a friend or family member. But then we remember KHEL’s history and the histories of our people – staff, kids, families, community – who have dealt with extraordinarily tough times and have always come back stronger. We hope that will be the case this time, too.

India is currently second in the world for Covid cases, behind the United States (third for deaths, behind the US and Brazil). Wealthy and well-to-do children across India are studying comfortably from home. Middle class students are struggling to keep up because they don’t have laptops, only smart phones. They’re still better off than most of LDA’s students because they have the other things they need to succeed – electricity, internet/wi-fi, free time, a quiet place to study and attend online classes, adult family members with steady jobs so that electricity, internet and other services are stable, and parental support. For KHEL families, if there are younger siblings and both parents are working outside the home, childcare and other home related work falls to the girls, cutting into their study time. This includes time intensive chores like fetching water from a well or pump and collecting firewood in the nearby forest. The UN states that, worldwide, we are already seeing an increase in girls being forced into marriage since they can’t go to school. The better we can teach remotely, the less likely this is to happen to our girls.

It’s always been our policy to adapt to changing circumstances, and that’s no different now. Other schools use Zoom and related apps, but these don’t work for our kids because not every family has a smart phone. We put together, and continue to refine, a 3-tier system to teach via smart phone, regular phone, and no phone, concurrently. Manju, our Headmistress, coordinates the academic side of our 3-tier system. All families in our community regularly deal with no electricity and erratic internet, so even if they can afford these things, there’s no guarantee of having them all the time. A note about the word ‘illiterate’: we mean not being able to read or write in the local language which is Hindi. Many migrants and people in our community have expertise in arts and indigenous sciences that don’t require reading and writing, as their skills are taught via oral traditions and apprenticeships. These skills range from how to build a hand loom to what plants work for which herbal remedies, and many other talents besides, but they do not help our children to gain the education they need to succeed in the world outside their immediate community.

Tier 1 – Smart Phone Group: Tier 1 parents have fairly stable labour jobs such as house painter or vegetable seller. They may be self-employed or have their own small business, and the mothers usually stay at home with the children. In general, their homes may have a few rooms, are ‘pakka’, meaning cement over brick, with cemented floors. There’s a bathroom, a kitchen, and either a well or city water. They have access to and can afford electricity, internet, limited wi-fi, and a family smart phone. Everyone gets to eat every day. They may have had some savings that helped them through the early part of the pandemic, but those funds are now used up. Teachers have What’s App groups with these students. In addition to academics, our teachers give general advice and support to the kids and their parents. Tier 1 kids send KHEL photos and videos and take part in fun activities that their teachers organise for them, which we share with you on Facebook and Instagram.

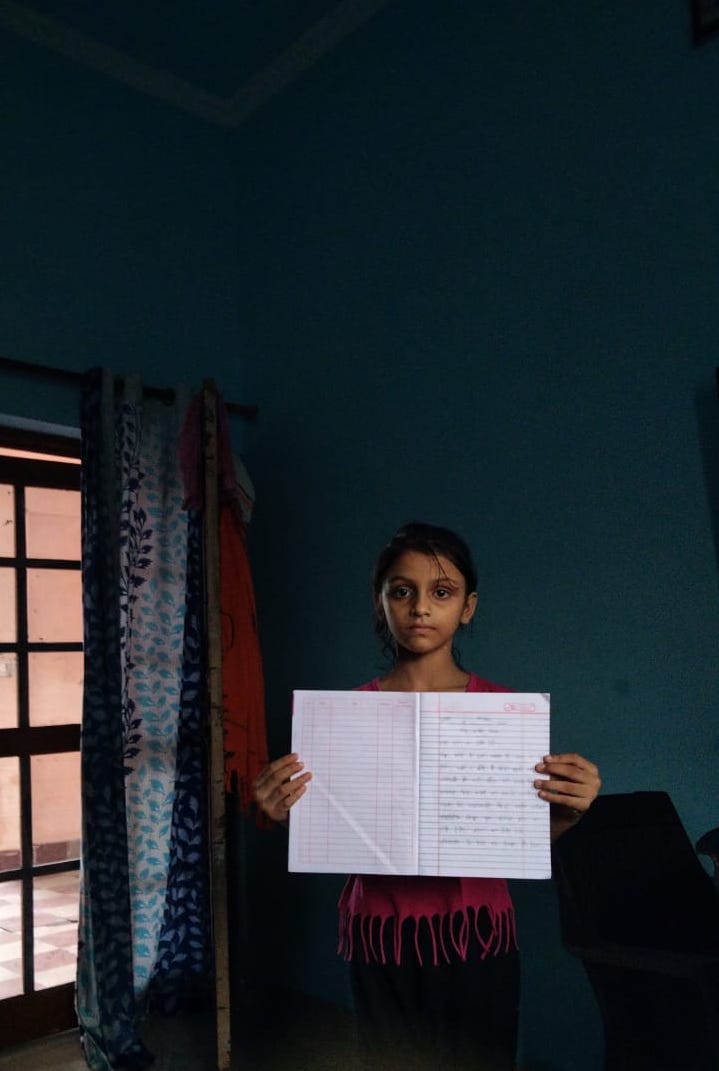

Our Tier 2 kids don’t have much room in their homes; note the bedding piled up behind them to make space for daytime activities.

Tier 2 – Regular Phone Group: Tier 2 families may or may not have two working parents. Their jobs are erratic and based on seasonal farming or construction cycles. Their homes are small, possibly 2 or 3 rooms, and most rooms are multi-functional. There’s usually a latrine style bathroom, and access to a deep bore well which may not be on the property. They may prefer to cook outside using collected firewood to save on cooking gas. Sometimes the homes are ‘pakka’, sometimes they’re partly ‘kaccha’, meaning bare brick, but floors are usually cemented. There is usually enough food for everyone, but it may occasionally be limited. The men and boys eat first, then the women and girls. Usually the mothers are illiterate, and fathers maybe can read and write. Although we were in touch with these families during the lock downs, teaching was challenging via regular phone, but we are teaching them now. Teachers communicate with our regular phone students by calling them to see if they have any questions about their schoolwork. These children may chat about other things with their teachers but mostly they only talk about academics. The teachers talk to the parents in this group more than they talk to the students, as Indian children have a certain kind of respect for their elders so firmly ingrained in them that they have a hard time speaking directly and openly to their teachers.

We don’t have photos of our Tier 3 students’ homes because they don’t have phones to send us photos. Just outside LDA’s gates you can see all 3 home types including an unfinished brick home with a tarp roof. Kids who live along the edges of Shiv Puri Colony may not even have unfinished brick walls. Often their walls are made of wood scavenged from the forest and lashed together with rope.

Tier 3 – No Phone Group: It’s not just the cost of the phone that stops our Tier 3 families from having one; families need to be have access to and be able to pay for electricity and internet. Whenever the seasonal cycle (of farming or construction) is over, they might go home to their villages. They are daily wage earners (if they don’t earn, they don’t eat), hauling bricks on construction sites, sowing and reaping local crops, or doing other labour that needs no training or special skills. Usually both parents work. If they’re settled in the community, they will have a small, 1 or 2 room home. There won’t be a dedicated space for cooking; sleeping gear is packed away in the morning so there’s space to prepare food over a small wood fire that can easily be taken apart when the space is needed for other activities. Walls are bare brick, and floors might be dirt. They don’t have a bathroom or water. Their homes usually border the forests behind our community, which they use as a bathroom and where firewood is collected. Often, these children come to school hungry, and girls are anemic. If families are truly migrant, they’re probably living under a tarp in the forest where they get some protection from the elements. Tier 3 kids are usually on their own during the day since both parents must work, so older siblings are responsible for their younger siblings. Before the pandemic, sometimes children from this group would turn up at LDA because they would see local kids going through the big gate and they were curious. We’ve had kids come to us at 12 or 13 years old with no reading or writing skills. We do our best for them, just as we do for every other child who wants to learn. In their home lives, literacy is mostly irrelevant as it doesn’t contribute to putting food on the table, but the parents are just as keen to improve their children’s lives as our better off and better educated parents.

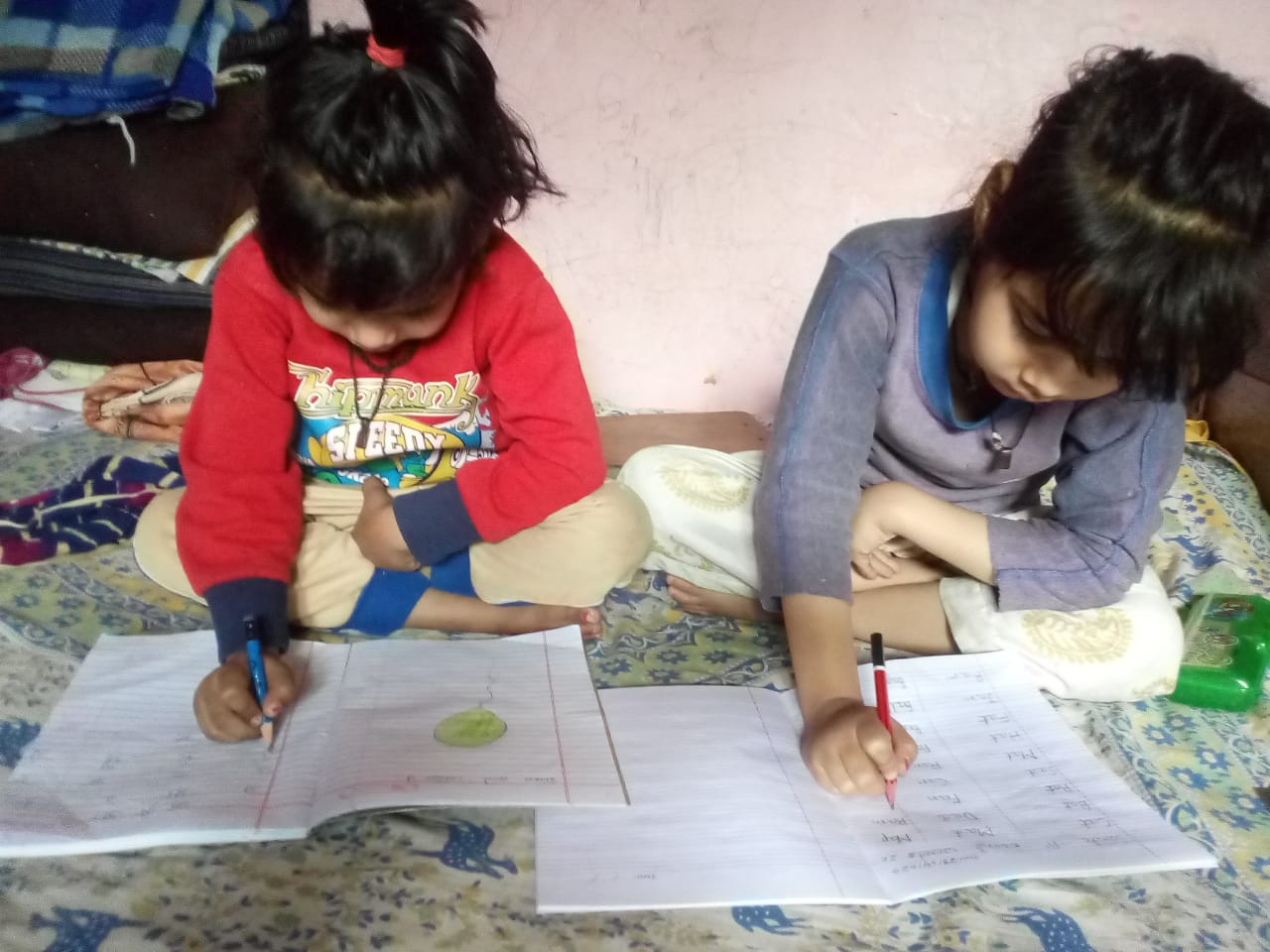

Sarik and Sarika studying at home. They have a thin mat to protect them from the cement. They have no other place to study.

We didn’t know how many of our Tier 3 students had stayed in the community until the last lock down was lifted. Then, our kids with phones started letting us know which of the no-phone kids were still there. We were overwhelmed to discover that our kids, independent of any instructions from us, were reaching out to their less privileged classmates. Here we are, thinking they’re ‘just’ kids, when the reality is that because KHEL offers an extraordinary level of support to our families this is what our kids have learned to do. They are helping to raise their own village.

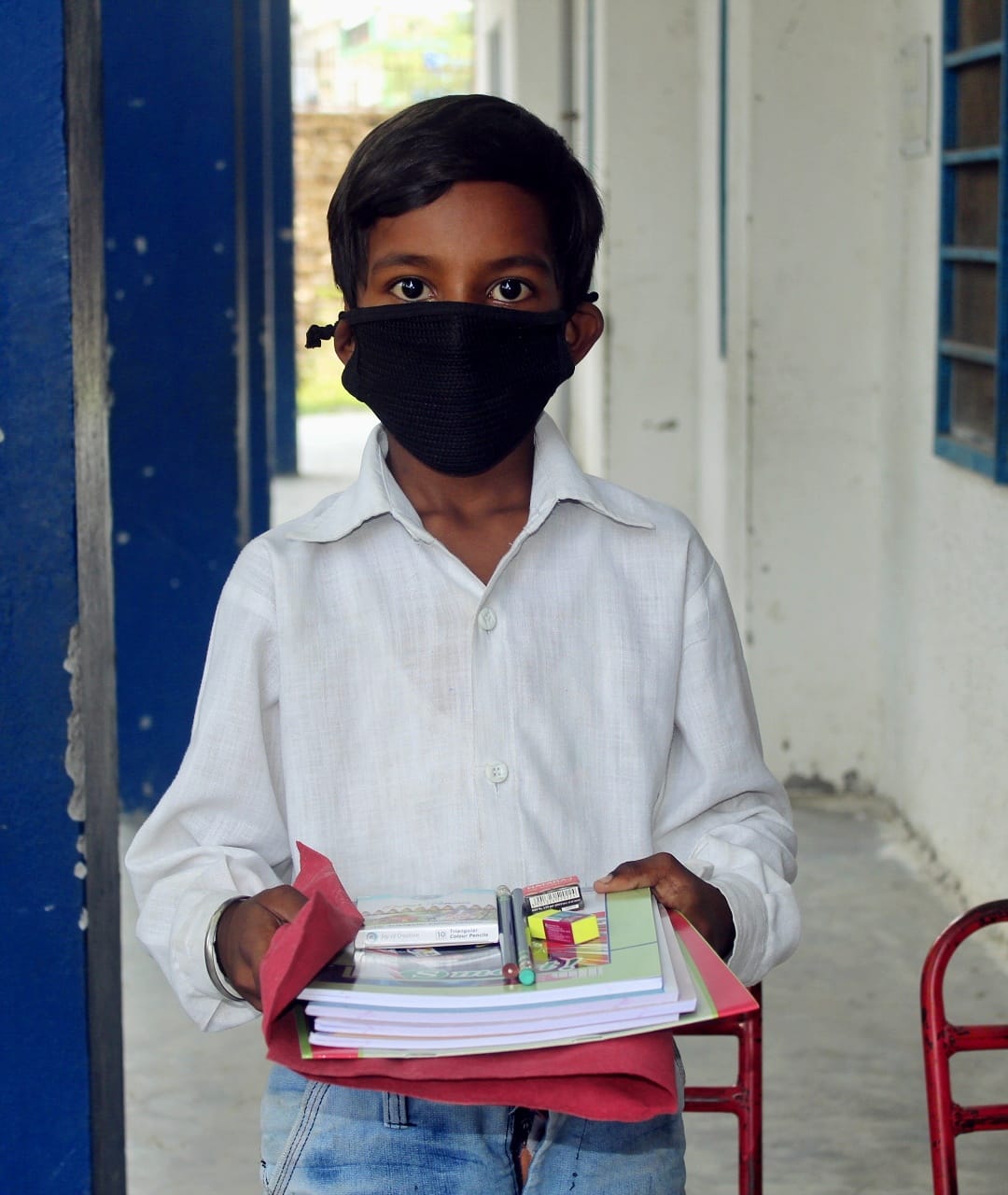

So that’s our Three Tier system, and some of the issues we have to consider while figuring out how to continue teaching our kids. This structured system is working because of other support we are offering. As the lock downs lifted, we realised that since parents hadn’t been working, they had no money to buy school supplies. We bought bulk school supplies from Suman Thakur, an LDA graduate who has a small stationery shop out of her home near LDA, helping her to stay in business. Suman put the school supplies together in individual packages so that it would be safe and easy for our kids to pick them up from LDA.

Of our 273 students, 204 were able to come to LDA to pick up supplies (206 families have a smart phone, 44 have a regular phone, and 23 have no phone. Some families have temporarily left Dehradun, but they’re still registered as LDA students). In order to encourage the students to take part in studying (because kids will be kids!) we included small treats and snacks. Because the jobs many parents have are erratic, we will have to repeat this by the end of the year so that kids continue to have school supplies. Our kids have been passing textbooks to the class below them, so most children now have at textbook. We hope this continues, as new textbooks aren’t available in the market. Cost for school supplies for our kids: INR60,000 (Euro689/USD817).

Once the monsoons tapered off and restrictions loosened, we set up times at LDA for teachers to meet safely with their students and parents outside, wearing masks, using a lot of hand sanitiser, and maintaining social distancing. Due to the 50% capacity rule, not all teachers can be at LDA at the same time, so it takes about 10 days to go through the cycle of kids dropping off their notebooks, sanitising notebooks, teachers coming in a few at a time to correct homework and print up new homework, and for the kids to come back to school to pick up their new set of papers. This cycle occurs about twice a month, with some days in between for the kids to do their work and for teachers to check the last set of work. We must comply with government safety protocols, which is, of course, the sensible thing to do, but there’s a monthly cost to all the safety supplies: INR10,000 (Euro116/USD136).

‘How to Teach During a Pandemic’ is currently our biggest project, but we have had other things going on, too.

Beni, KHEL’s General Manager, and Kamli, Beni’s wife and our City Councilor, distributing rations to our friends at a leprosy colony in Dehradun.

In July, we distributed dry food rations to three leprosy colonies (INR38,000/Euro437/USD517). We also completed the complicated bureaucratic process of renewing LDA’s recognition for 2020-2023 – we can’t teach without this. There are no photos for that since it was mostly just Beni getting exasperated while trying to upload forms to a government website (INR76,000/Euro874/USD1,035).

RDI, the non-profit arm of HIHT, supplied us with hygiene kits for our older kids. This was especially helpful to our girls who have reached puberty (free).

Beni with workers after installing water tanks on our roof. The stairwell was too narrow so they designed and built a manual pulley system.

Since the lock down lifted, we’ve had construction going on at LDA. The fire department told us that we must hold 10,000 litres of water on our roof (that’s about 2,700 gallons), along with other equipment in case of a fire. This water can’t be used for other things so it’s in addition to our underground water tank. We used up all our emergency savings fund to pay for this work (INR242,000/Euro2,774/USD3,287).

Our architect, Mr. Maindola, talks to our contractor, Rajinder, and Beni about how to solve the problem of an underground stream destroying our new underground water tank.

LDA was built in 1988. Apart from maintenance there are new requirements every year. Last year we raised funds specifically for some of these required upgrades. There were unexpected expenses that occurred due to additional drainage in various parts of the school grounds to keep heavy monsoon rains in check, and a previously unknown underground stream that we found out about when we dug down to install the underground water tank. We can’t move the tank to any other location so we’re building an underground support system to keep it from flooding. There were also repairs because of a burglary – during the strict lock downs, we weren’t allowed to have anyone at LDA, including guards. Unexpected cost for these projects: INR160,000 (Euro1,850/USD2,192).

***

We will not abandon our kids to forced marriages, to a lifetime of hauling bricks by the side of the road, to poverty and poor health because they can’t earn a decent living, to another generation of wasted talent. Whether they live in a multi-room house or under a roof made of scavenged tarp, every one of our kids deserves a better future. Without education, there’s no hope of that.

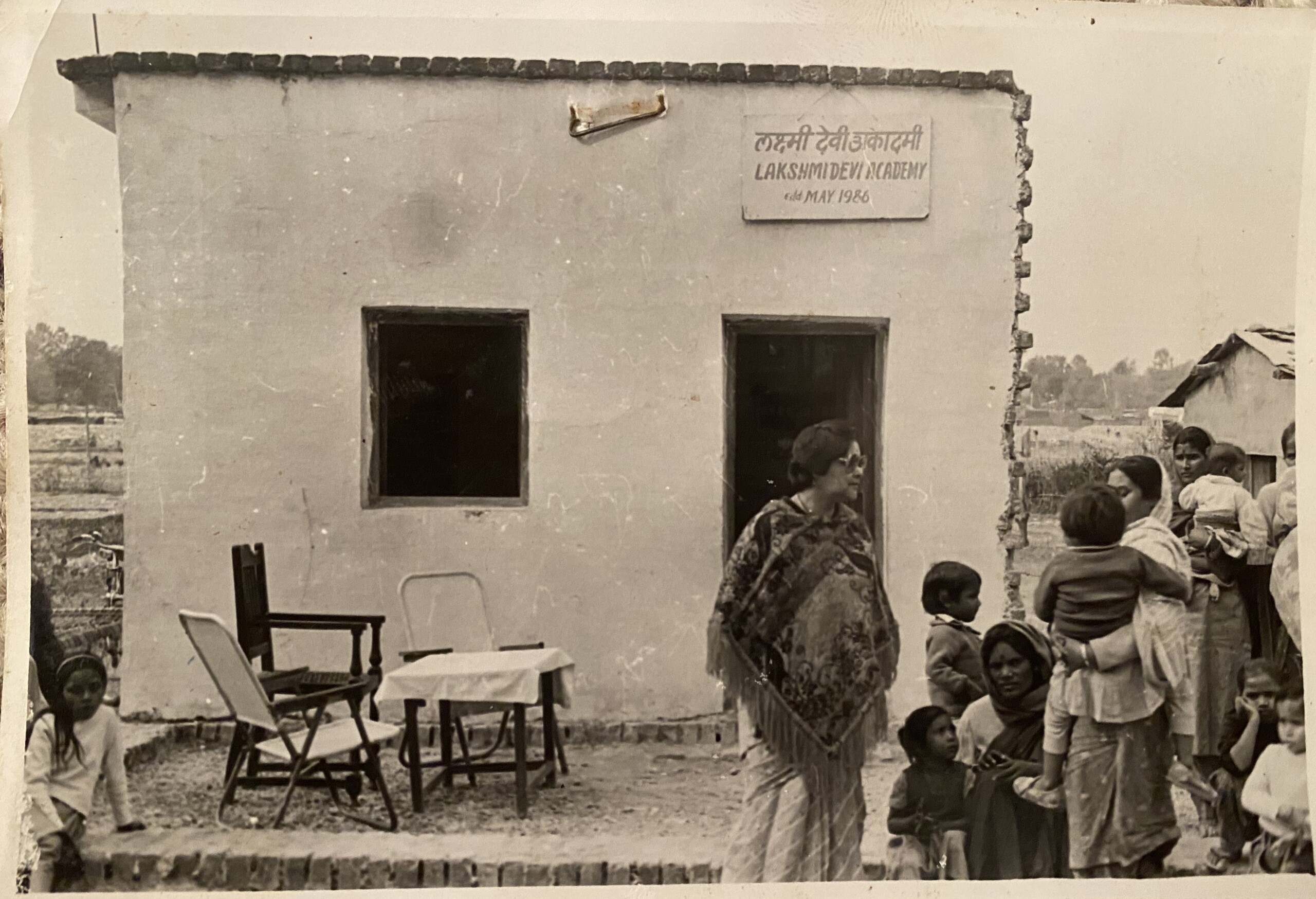

Whether it’s Ammaji giving milk to kids and teaching them under the trees sitting on bare ground, on carpets tossed on the dirt, in a one room schoolhouse, in a one-story building, in a two-story building with a playing field and electricity, or in their homes during a pandemic, we will adapt to changing circumstances and find ways to keep teaching our kids. Because each and every one of them deserves the right to make a better life for themselves, their families, and their community.

Please help us give them hope for their better futures.